Welcome to interview no.1, where I - author Steve Shahbazian - interview the great and the good.

Having just started a blog, I was faced with the question: what do I blog about? Like authors before me, I thought about book reviews or essays on whatever came to mind. But how much do people want to hear my voice?

So, I had another idea. How about a periodic series of interviews about literature and dystopia?

This would be a nice way for readers to hear about subjects related to the themes of this blog from people within the literary world to provide another perspective. Therefore, although the interviews will be hosted within my blog, the views therein will be those of the interviewees and not my own. After all, it’s always good to hear different viewpoints.

So without further ado, onto my first interview. Please note that this is the first time I have ever conducted an interview, so any inelegancies are purely my own.

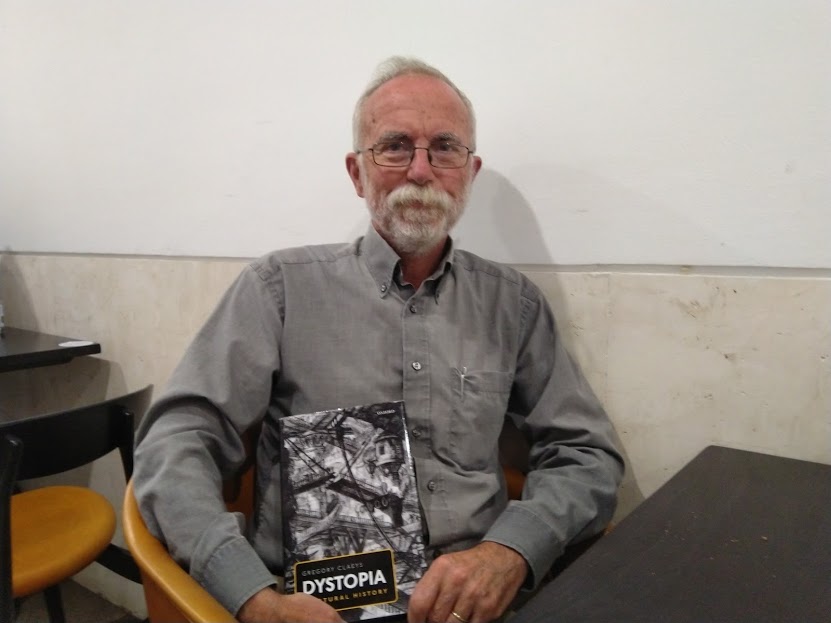

I’m at the British Library with Greg Claeys, who is the Professor of the History of Political Thought at Royal Holloway College and the author of Dystopia: A Natural History, published by Oxford University Press – the world’s first monograph devoted to the concept of dystopia – which I heartily recommend.

Greg very kindly offered to write a foreword to my novel Green and Pleasant Land after I approached him out of the blue, for which I am eternally grateful. With dystopia becoming very popular in the last few years and sales of books like Nineteen Eighty-Four, The Handmaid’s Tale and Brave New World soaring, I asked if he would like to join me to discuss the idea of “dystopia” and the relationship between literary dystopia and real life.

Professor Claeys, thank you for joining me.

The Road to Dystopia – an Intellectual History

I thought I would start, as you’re the Professor of the intellectual specialising in the history of socialism and utopia, what brought you to the study of dystopia?

I started my career in the late 1970s and finished my PhD in 1983 concentrating on early British socialism. It turned out that not too many people worked in this field and I discovered an immense treasure trove of materials. I spent five years interpreting that and produced two books as a historian of early British socialism.

What were these books about?

The first book, which is on Owenite political economy appeared in 1987, the second book, which is on Owenite political thought in 1989. 1989 is a singularly totemic iconic year – the fall of the Berlin Wall – probably the worst moment in history to dress yourself up as a history of socialism, just as the entire system comes collapsing down around our ears!

How did you become involved in the history of utopia?

In the years before this (particularly in 1984 – which resonates because of Orwell’s great novel), I had branched sideways into both utopian and dystopian fiction, but only by dallying with certain themes that came up. There were se many conferences in 1984 about the applicability today of Orwell’s novel, but I hadn’t really gone full time in that direction.

When did that happen?

This occurred only in the beginning of the 1990s. As historians tend to do, I found myself studying periods further back in time. The starting point in my history of Owenism was around 1815, so I began to look back to the late 1780s to the 1790s. I wrote a book on Thomas Paine, who is the most famous British radical in the period of the French revolution and then began to look further beyond Paine to the 1780s and 1770s. In doing this, there was a kind of conjunction of the interest that arose from Nineteen Eighty-Four, the broader interest that arose from investigating the history of socialism and looking constantly for intellectual trajectories.

Did you go straight from writing about utopia to writing about dystopia?

No. Around 1990, I started to look seriously at utopian, but not dystopian literature. I was trying to sketch out an intellectual narrative, which placed what I would call “utopian republicanism” on a spectrum of republican ideas.

At this time, the two main modern interpretations of political thought were Quentin Skinner and John Pocock and this was my way of tweaking both what I understood them to be doing as well as putting a label on what I had been doing in relation to their work. Their concerns were not by and large the same as mine, with both of them being broadly liberal figures. My concern was with how we could align what we would perhaps call a history of the left with their history of early modern and modern political thought, which had mostly left out the left.

I published a collection of primary sources first called Utopias of the British Enlightenment, then went on to publish another eight volume and several other sets of primary sources and worked through this material really well into the late 1990s.

What changed after this?

The year 2000 had great symbolic value for anyone who works on the utopian tradition. The turn of the millennium invites comparison with millenarianism, which is one of the most important antecedents of modern utopianism. I was involved for the better part of five years staging what was then the largest museographical exercise in utopianism: an exhibition, which was put on at the Bibliotheque Nationale de France and the New York Public Library. We had plenty of time to look over the history of traditions with Lyman Tower Sargent, a well-known scholar in utopian studies. It was at this point, I was trying to envision how to engage with utopian literature from a historical point of view.

That's quite a sideways move. What was your purpose in doing this?

For some interpreters of the novels, this was a really illegitimate, fanciful way of proceeding. If you treat many – though certainly not all – utopian texts as novels of ideas, you see that the fiction is often just a device for conveying an image which is critical of the existing society and a counter image of what the author envisions a much better future would look like. That’s a standard trope. It doesn’t cover all the fictional forms that utopia assumes by any means, but a very large percentage of them.

Writing about Dystopia – the Orwellian influence

What led you to move into writing about dystopia?

It started to become apparent right about the same time – certainly by 2005 – that there was going to be a much more marked shift in the direction of dystopian writing among contemporaries. Now, this won my heart because I had gotten my toes wet writing a few pieces on Orwell – Nineteen Eighty-Four and The Lion and the Unicorn in particular – around 1984. So, I went back to Orwell and began to think about the book that became Dystopia: A Natural History.

How long did it take?

The gestation period was pretty long – about eight or nine years; five years for the writing alone. It’s a long book: around 270,000 words.

Why did the book take so long to write?

The book was written in the order the sections and chapters now appear. I didn’t, as you might have imagined, think of the Orwell chapter – which is the single largest engagement with a literary figure in the whole book – first. I didn’t start this until I had written the better part of the rest of the book. I had written the long theoretical and methodological section in the first third, the engagement with real-life totalitarian societies in the second third, the literary introduction, which engages with the secondary literature on dystopia, and the whole pre-history up to the 1940s, before I sat down to write the Orwell chapter.

It was at this point that the scales kind of fell from my eyes. It’s a wonderful moment of the sort that occurs very rarely to an author’s life. I realised, when I reached the section on a little known essay called Notes on Nationalism, which Orwell wrote in 1945. I could then see that the entire structure of the first section, with the emphasis on group psychology in particular, was exactly the pre-history of the writing of Nineteen Eighty-Four.

What was so significant about this particular essay by Orwell?

Orwell was trying to come to terms with the issue that becomes the overarching theme of Nineteen Eighty-Four: the fruitless endeavour, in a totalitarian society, of the individual to pit themselves against a ruthless, all-consuming, monopolising, collectivist machine of a society – of what is a satire, essentially, of the Soviet Union under Stalin.

I realised that this was the main theoretical insight that Orwell had in mind when he set about writing Nineteen Eighty-Four and it became immediately clear to me that I was extending what Orwell was doing in Nineteen Eighty-Four. I didn’t go back and rewrite what I had written about group psychology, but it was extraordinarily gratifying because I had long been an admirer of Orwell.

How do you see Orwell?

I see Orwell as a figure of the left and not as a conservative or a reactionary. I disagreed with this misappropriation of Orwell, which signified much of his reputation in the 1950s and 1960s and led a large proportion of the left to distance themselves and become extremely hostile to him.

Environmental Dystopia

Environmental destruction has been a major theme in recent dystopian writing. How has it informed your thinking on the subject?

I had had a long-term interest in the environment and every year since the 1990s, in the main course at my university, which is called “Modern Political Ideas,” I have a final lecture, which started out in 1991 as the “Green Utopia.” Every year from about 2000 this lecture became a little more pessimistic, a little more shaped by misgivings and by a sense of foreboding. The climate data as it then was – very crude compared to what we have today – starting to indicate a much graver threat than the environmentalist / green movement had indicated from Chernobyl and Waldsterben in the 1970s and 1980s.

It then became clear to me that the end station – which was of course portrayed in the “dystopia of my very own” at the end of my book – is environmental devastation. If we see Orwell and the focus of the 1930s and 1940s as a satire on extreme forms of collectivism, then there is also a narrative which develops in the 1960s and 1970s, which begins to bring in other themes – satires on computerisation, on the overwhelming of the human in the light of the machine, of the eradication of the human by the post-human by creating cyborgs and so on. By 2000, this type of writing was heading very much in an environmentalist direction.

By 2008, it was clear that the warning signs were starting to flash more loudly and more alarmingly than ever before. This was nothing to do with the financial crisis and everything to do with the data that was coming in about so-called climate change and so-called global warming. It was becoming evident that this was the wrong language to use and that we are facing a catastrophic environmental breakdown, which may well end up with the extermination of the human species – and as soon as three decades from now.

The news since then has become ever graver, for example the fires in the whole North of the world. In the Arctic itself, the rate of temperature change is well above twice the global average, which is now about 1.1 degrees Celsius. The fires in the Siberian tundra threaten to unleash probably the single most threatening tipping point in the millions of tonnes of methane that are buried under the tundra: methane is a much more poisonous gas than CO₂. This could elevate global temperatures very dramatically and very sharply almost overnight. This has happened before in history.

The narrative that we had been very comfortably working with from Kyoto through the Paris Agreement of somewhere between 1.5 and 2 degrees global warming as sustainable turns out to be the wrong set of calculations. The narrative is that the worst-case scenario that was projected in 2000 now look to be, not only likely, not overwhelmingly probable. Those worst-case scenarios point to a global warming of between 4 and 5 degrees Celsius as early as 2050 and this is not taking into account the spikes which may occur, such as methane gas release on dramatic scale.

Would this alter how you had written your book?

The dystopia at the end is an environmentally-driven dystopia and it takes this as a fundamental premise. If I were to write the book again today, I would have speeded up the process and would have been much more dramatic in the prose as to how we counter it. If the warming should come so rapidly that we can imagine 10 degrees Celsius in a single year, then we can imagine summers in Europe at 50 degrees Celsius: the entire infrastructure would melt and hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people die and it would be a case of absolutely unparalleled social, political and economic catastrophe. It’s not only not impossible; it’s becoming increasingly likely. So, if I were writing this book today, I would have drawn this out much more substantially.

Utopia and Dystopia

You’ve talked about your work on the utopian and dystopian traditions. As your book explains, they have a different history. The term “utopia” was famously coined by Thomas More in 1516, but the origin of dystopia as a distinct concept emerges much later. For people not familiar with the concept of utopia and dystopia, could you elaborate on the origin of the term “dystopia”?

There are a few early uses and variant spellings in those early uses in the eighteenth century and nineteenth century, but they are of negligible importance to modern scholars or readers of dystopian fiction. The term itself doesn’t come into common circulation until the 1970s and 1980s.

As late as that?

As late as that. There are various descriptions of it after that, some of which correspond to the debates about what the term “utopia” means – which is by no means fixed – and others of which are a bit more wide-ranging.

What was your purpose in constructing an intellectual history of the concepts of utopia and dystopia?

What I tried to do in assessing the term was to attempt as a historian to engage in a dialogue with literary scholars. Most historians don’t read literature as a historical source and most literature experts don’t read a lot of history, so I was particularly concerned to ask a question: if you presume that both utopia and dystopia are not only about fictional or imaginative entities, but that they also describe some kind of potential or real existing state, then what happens to your appropriation of the subject?

Utopia is not just nowhere and it’s not just fiction; it’s also communitarianism, that is to say people’s coming together and living in a way which corresponds to some of I call “enhanced sociability.” People are brought closer to one another and value the group relationship more than the emphasis upon individualism, which is a common note in the modern period – in the more advanced societies anyway.

And dystopia?

I was trying to set up a dialogue between literature and history to ask the question: if dystopia now is the representation of supposedly bad or evil societies (which is the common or garden definition you could get from a lot of texts), how does that correspond to the notional object of many of the fictional dystopias – the real, existing dystopian societies?

Most of these real-life societies fall under the rubric of what we today call “totalitarianism,” which is an extreme form of collectivism. For short, most people concentrate on the Nazis or Stalinism. There are many other forms, but these are the two that are the most destructive.

The crucial question I wanted to ask was: if we place these societies side by side with the literary descriptions of what makes these societies dystopian – the key instance being Nineteen Eighty-Four – and look at the actual functioning of these societies, what does fiction tell us about real life and what does real life tell us about fiction?

Orwell’s Continued Relevance

In real life, Orwell was accused of exaggerating what had happened in real life and that his depiction of Stalinist tyranny was over the top. How did you respond to that?

In the case of Orwell, I very much had on the backburner the frequent complaint made in the 1950s and 1960s that his famous descriptions of the torture scenes in Room 101 was completely over the top. And the left was very much concerned to argue that there was no way in which Stalinism and National Socialism could be bracketed in the same category. The left resolutely refused to use the term “totalitarianism” as a catch-all phrase for describing both regimes. It wanted the enemy to be Hitler and for Stalin’s mistakes to be accorded a completely different kind of status.

I didn’t accept this argument, which had gotten me into hot water with my friends and colleagues on the left, because, the similarities between these regimes were uncomfortably close. Both engaged in very wide scale mass murder, both engineered and sustained mass terror.

Stalinism engineered a regime of fear as a way of dominating its population even more than National Socialism, which is the claim I make in the book and which got me into even more hot water with the left. By and large the relationship between the average German and the Nazi party was not one of fear and hostility, whereas in the Soviet case the permeation of fear through the use of the secret police was much more marked. You can play infinitely with the numbers who are killed by both regimes – there’s a certain amount of mileage to be gotten out of this – but I don’t think that ultimately is the most important thing we need to understand.

How would you say this is relevant to today?

We’re in the middle of a constitutional crisis, in which allegations of fascist coup have been made, but this is no laughing matter. The moral of the most horrific story of the twentieth century may well be coming back to haunt us – not necessarily a totalitarian regime or anything like that, but the possibility of democracy sliding into extreme right-wing regimes is as present today as it was in the 1930s and we ought to be concerned. It’s a completely separate concern from the environmental issue – there’s too much on our plate, really.

It has become a commonplace that Orwell’s observation of totalitarianism of Stalinism and Hitlerism of being identical but, as you observed, all these totalitarian states are totalitarian in their own unique way. Each has its own individual style of rule and each – even on a small scale – is remarkably nasty. Take the Cambodian…

Cambodia’s a terrifying case.

There are broad similarities – the secret police, the one-party state, the camps and so on – but each has its own unique flavour of brutality. What was so shocking in your book was in bringing home the way in which no fictional dystopia can ever remotely approach the horror of its real-life equivalent.

The regimes we are speaking of – Orwell, of course was not aware of the Cambodian case – were all much worse than the fictional portrayals. The single most piercing moment in the torture sequence in Nineteen Eighty-Four – the placing a rat in a cage – had been done in the USSR. Whether Orwell knew this or not (I tried to pursue this for a long period of time) is impossible to say, but we do know he hated rats above all things, so he might have conjectured this would be the worst thing anyone could do – but it had actually been done. And when you consider the scale and the actual means of torture, it’s very much worse in reality. So my answer to the charge that the torture scenes in Nineteen Eighty-Four are over the top is: no, not at all. If anything, they are underplayed.

Then there’s Auschwitz, which doesn’t enter into Orwell’s calculations in Nineteen Eighty-Four, but if you know anything in detail about everyday life in Auschwitz – not just the numbers killed and so on – but the degradation and barbarisation of the inmate population – it far exceeds anything in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

The twentieth century has been truly horrific. I was reading Ordinary Men by Christopher Browning and The Gulag Archipelago by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and real-life inhumanity far exceeds anything found in a fictional work. As a writer of fiction, there are limits to what you can depict, because a realistic description of dystopia would be too unpleasant for the reader to want to read. People ultimately read fiction for pleasure, so fictional dystopias tend to take on something of a comic book quality. They can never come close to the real thing.

Which is why one should read history.

Absolutely.

In addition to reading fiction, of course.

As someone that loves reading history, I absolutely concur and, as a novelist, I applaud your efforts to bring together literature and history – two things that I love. An intellectual history of fiction and how that fiction relates to the real-life events it depicts or satirises – the object of its satire or commentary – really does tell us something about the world, not so much in a factual or descriptive sense, but about how we imagine our world and what it means to us personally. Your work certainly draws that relationship out.

Dystopia as Utopia – Huxley’s Brave New World

We’ve talked about Orwell, let’s talk about Huxley. In many ways, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World embodies the ambiguous relationship between utopia and dystopia. On the one hand, it satirises Fordism and mass culture, which he disliked; on the other embodies some of his ideals, such as town planning and eugenics, which he at times espoused. What is it that makes his world dystopian?

This is a tricky question because it is such a richly textured novel. Famously, when students read it the first time and you ask them “Is this a utopia or a dystopia?” they say, “Well, you know, sex, drugs, the feelies; it’s got to be a utopia, right?” and then you probe a little bit further and they realise they’ve been taken for a ride. It’s supposed to be portrayed as a dystopia – or is it? It’s actually both combined in a lot of interesting ways.

In both cases, the motive of the ruling group is pretty much the same: both ruling groups attempts to obtain and maintain power. The dominant group in Nineteen Eighty-Four – the members of the Inner Party – are motivated by power worship. As long as we understand that their aim is to keep their society well-ordered, the rulers of Brave New World – the Alphas – are in a similar situation. In both cases, they benefit from power: they lead relatively privileged lives, they have access to goods and services and so on that most of the rest of the population does not have.

The strategy whereby the majority of the population is kept in a subservient position, however, is very different. The proles are kept at a low standard of living and ill-educated – their leaders are knocked off in Nineteen Eighty-Four – while eugenic engineering ensures that the lower classes in Brave New World only know what they have to know to do the jobs they have to do. They can never become rebellious as a consequence.

Power worship in modern society is no different. It assumes a slightly different form in the machine age, because it becomes mechanised and machinelike, as it’s associated with the use of machinery and thinking mechanically as a group – as a collective kind of mind – but at the same time, the motive is timeless, it’s age-old. Huxley and Orwell had some correspondence and had some falling out – although there is some evidence that Orwell at the end of his life came around to part of Huxley’s view. The future is more likely to be Huxley’s vision, which is much more recognisable to us today than the vision portrayed in Nineteen Eighty-Four of a brutal dictatorship.

Is it a utopia or a dystopia when you have soma and free sex all the time? This boils down to a question Huxley posed time and time again: would we rather have order, giving up our freedom, or would we rather have the right in a much more disorderly society to guide our own affairs and have a sense of free will. This is John the Savage postulating this line in Brave New World.

What would you say Huxley was satirising? Orwell did once consider Brave New World a satire of collectivism, but the main targets seem to be closer to home.

By and large, Brave New World, published in 1932, is a satire on capitalism in the 1930s – it is not a satire on collectivism. I tried to probe this as far as I could to ascertain if there was any intention to satirise the Soviet Union. Aldous Huxley was well aware of what the Soviet regime was like and at certain points before 1932, he sympathises with the need for centralised planning and so on, but he seems to go off the boil in any kind of enthusiasm for the Soviet regime by 1931 or 1932 or so.

That is not the butt of the satire here. The butt of the satire is a society, which is essentially guided by hedonism, which Huxley brilliantly sees as the dominant ethos of modernity. You can trace this back to the early eighteenth century and the decline in the faith in God, which was the basis in the huge surge in the belief hedonism is the only life it is possible for a human being to live. Huxley doesn’t of course accept it. That’s the brilliance of the satire in Brave New World.

Huxley’s idea is that the domination by advertising – the repetition of certain formulae about how we should lead our lives – and the satire upon patterns of consumption – ending is better than mending, for instance – is absolutely pertinent to where we are at the present day. Is it a utopia or a dystopia? The answer is really: it’s both at the same time.

I must admit, I absolutely love the novel. For all its flaws, it’s…

A brilliant work.

Yes, brilliant work. You’re point about the difference in what Orwell and Huxley were satirising is highly apt. Although we talk about the 1920s and the 1930s as the “interwar era,” the two decades are in some respects quite different. The 1920s – in the US, the “roaring twenties” – has quite a lot in common with today – such as democracy, consumerism, the growth of leisure – whereas the 1930s is more the decade of depression and totalitarianism. Orwell’s novel Keep the Aspidistra Flying, with its emphasis on advertising…

Which Orwell despised.

Yes. Has more in common with Brave New World, and you can see those things today.

The totalitarianism of the 1930s and 1940s seems less applicable, but we will want to consider the Chinese case in particular. The rise in the use of face recognition technology, particularly the Chinese alignment with this with its social credit system, whereby – and this is Orwellian in the classic sense of the word – if you cross the street against the red light, you get points ticked off against your social credits scale and you may not be eligible for state loans or educational provisions or whatever. This is not just surveillance, but grand-scale management in a way that makes the telescreen look like a child’s toy.

And we are facing this in London ourselves. Not many yards from where we are sitting, one of the first major experiments in facial recognition cameras in Kings Cross is being played out. There are civil liberties groups making the claim that, firstly the technology is extremely clumsy – if you’re not white, it tends not to pick up on subtle nuances – and secondly, the threat of pervasive surveillance, which we have tended to downplay.

I remember in the year 1984, we discussed the role that CCTV cameras played. At that time, there were not nearly as many as there are now. Now you can walk across the whole of London and not be out of line of sight of a camera the entire way. We’re the most supervised society in the world in that sense, even more than China. This means again that Orwell remains extraordinarily relevant. Whether this is sowing the seeds of a future totalitarianism or not, I want to start ringing the alarm bells: the government could abuse the system like this extremely easily. The technology may be neutral, but the politicians are not.

We know that it will be used for example to scrutinise crowds in demonstrations. Demonstrations which are perfectly peaceful and legal and there is very widespread surveillance of the crowds. Obviously, the police are building up a database, as they want to be able to identify “activists.” This is a legal activity up to the point at which the law is broken and one could of course conjecture the police have every right to take your picture – but to record date on all those engaging in a peaceful protest? This is a threat to democracy and, given all the other threats to democracy, we have to take all these challenges at face value. Literally, in this case!

I’ll use that joke somewhere!

The Psychology of Totalitarianism

In your book, you look at group psychology. A key component of a ruling regime is manipulation of thought and emotion through propaganda. What is it that makes group psychology so central to dystopian life?

I regard the approach to the themes through group psychology, in my own modest way, as one of the most original parts of the book. The literature on utopia is much more numerous than the literature on dystopia but, with the certain small exceptions in the literature on collectivism, at no point is an approach through group psychology taken to be central to understanding the relationship between utopia and dystopia.

How does group psychology, then, illuminate the relationship between the two concepts?

I tried to pose the question: don’t dystopian and utopian novels and real-life scenarios portray a very peculiar kind of group? In both cases the individual renounces some right to individuality – to freedom, to doing things their own way – in return for gaining something from the group: in the case of utopia, they seem to gain an immense amount but in dystopia, they gain virtually nothing back. Dystopia is a space dominated by fear and they live constantly with the fear and anxiety of being arrested, liquidated and so on.

It struck me that one of the ways of trying to do this was to approach this the way Orwell did in Notes on Nationalism. He looked at the problem through the relationship between the writer and the political party or movement. For Orwell, the writer is faced with a basic conundrum – writers on the left especially – you need to engage politically with the current problems of the age to the degree to which you adopt a party line, but then you run the risk of sacrificing your own individual perspective and becoming unable to be critical of whatever the party line happens to be. Famously, in Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, the party line changes all the time and it’s not a matter of truth. Winston Smith’s role in Nineteen Eighty-Four is precisely to ensure that what is “history” always accords at any one time with whatever the party line happens to be at that point in time.

What I think Orwell thought by 1944/45 is that individual authors had to be extraordinarily careful in their engagement with groups of any kind. Here, the political party is just an instance of a kind of group: churches, sects and many other kinds of organisations follow similar rules. I tried to account for what these rules were and ask certain some basic questions about what happens when we join groups. How is it that we can understand that our selves as individuals will have a perspective on what we are doing and that anything we see ourselves as being and any identity we possess will be adapted and rendered more malleable by our membership of the group, sometimes to the extent of being wholly negated?

I started off with certain basic hypotheses about identity. I used Social Identity Theory to answer the basic question we ask ourselves all the time and other people all the time, namely who are you? If you answer that question, you’re going to say, “I’m a white male, who lives in London, who is of a certain age, who lives in a particular neighbourhood, who has a particular religious / political affiliation, who supports a particular football team.” All of these are group affiliations, so the next question is: what is the “I” that we’re left with when you strip away the group associations? And how is that “I” separate from those group associations? This turns out to be a really interesting and complicated set of questions.

I think that is exactly where Orwell was in 1945. Notes on Nationalism is a very conjectural, haphazard and sketchy piece: it’s not very well thought-out but Orwell was really onto something. Unfortunately, he didn’t have the time to sit down and think it through, otherwise he would have been able to come up with a much more satisfactory label. The word “nationalism” simply doesn’t describe what I call “groupism” – that is to say the tendency of the individual in the group to give way before the norms and demands of the group itself.

As an author, I found the section on the patterns and trends in dystopian writing particularly fascinating. I was surprised firstly how many dystopian works there were and it was interesting to see the themes that run through them.

I felt I had a free hand here. There wasn’t an existing book on the subject. There are a few other texts in the field that engage with all the possible definitions of the concept of dystopia, then to set it against utopia, then to bring in both literature and history at the same time, and then to offer a history of where the concept is used and the way novels exemplify the basic variations.

This has the advantage of being able to do pretty much anything you want as an author, which is huge advantage. It has the disadvantage that you have to be really methodical about everything. I had to go over in much more detail about how the secondary literature evolves from the 1950s onwards – there are major trends there – because I was setting out to define quite a new field that hadn’t been treated comprehensively before.

The Dystopian Genre

Writing a dystopian novel myself, I realised there was a distinct genre of political dystopia. I had been influenced by the sort of novels you had surveyed, which are quite different from some other works classed as “dystopian,” which are more sci-fi / fantasy orientated, where the focus is on creating a fantastic world for aesthetic effect. You touched on this in your review, noting that some of the works were shading towards sci-fi. Yet, despite this, political dystopian fiction, is not recognised as a genre. So, it was really exciting to see how the genre has evolved and the commentary it has made.

It is one of the main reasons why I decided to stay clear of science fiction and, following Margaret Atwood in particular, draw a fairly firm line between more or less realistic dystopias, which take trends from the present and look at how they might pan out in the future, and leave out the most extreme kind of futuristic formulations. Science fiction is a much larger genre of fiction than dystopia and there are a great many dystopian works where there is a large element of science fiction, but you can’t do all of that in a single book and this was already getting out of hand in terms of length.

It’s really quite a massive book! It took me quite a while to read it: there was a huge amount of information, all of it really good. I found it very stimulating.

It’s always really interesting to see what authors make of it.

I really liked it. I was intrigued by how the theories of group psychology evolved. I was working on a series of essays on literary dystopias at the time and what was truly fascinating was the way I could take your discussion of Freud and apply it to J.G. Ballard’s novel High Rise. As he used Freudian metaphors, it was a perfect description of what he was doing. It was also a major relief to find out we’d both read the same works and come to the same conclusions – and even quoted the same passages! Particularly on the section about James Burnham’s influence on Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Burnham is really significant.

Dystopia Today?

I think we’ve touched on why dystopia has become very fashionable in the last three years, but I’m going to have to ask: at the end, you sketch out a dystopian scenario, which features some familiar themes, such as environmental degradation and the wealthy retreating into gated communities to continue lives of luxury, but also some unfamiliar themes, such as epidemics of psychic disease and cults of robot worship, including – and I have to say this is absolutely brilliant – a “robot Lenin.” What do you think the future of dystopia is?

If only I could write fiction! I would write that book!

I think you’ve got a great novel in there; you really have!

Well, as you know, history and fiction writing are two totally different activities and if you’re skilled in one, it doesn’t necessarily imply that you have any skill whatsoever in the other. Otherwise, I would have probably taken a crack at it by now.

That very short section – about five pages – is based upon the realistic dystopian presumption, taking trends from the present and projecting them fifty, sixty, seventy years into the future. If I had written it today, it would have been a little shorter and maybe twenty to thirty years into the future, because the environmental catastrophe is now looming much more closely. What I’m trying to do is to give a sense of realistically how the worst-case scenario would pan out.

Now, I’ve gotten into a certain amount of hot water because of this, because it looks really pessimistic. What I’ve done is in the spirit of the literary dystopia. I’ve tried to say, “If you were to write a satire on the worst-case scenarios at present and you were to take the leading themes – the environment, the next stage of mechanisation – so-called “robotization” – the transmutation of humanity to a post-human kind of condition, how would these play out?

I think the first of all these crises – the environmental – will far and away outpace the development of the others, so that it’s much more likely that we will go under as a result of the environmental destruction before massive robotization ever takes place, but I’ve fictionally played with that idea in that last section to adjust for that with the seventy years scenario, which makes the conjunction of the two developments is much more likely. They work very well with each other, because it’s very likely that, when the planet starts to heat up, large parts will not be inhabitable except by mechanical creatures: whatever farming, mining and so on that goes on there will only be done by robots. This works well, but only if the two developments work in conjunction.

This of course seems an extremely pessimistic scenario and I’ve come under a lot of fire from people in utopian studies for not offering an alternative. What I’m doing in the present book, Utopianism for a Dying Planet, is to offer that alternative. I hope it will be done in about eight months or so. Wait and see!

I find it odd that you’ve come under a lot of fire. I was reading another really good book, The Ministry of Truth by Dorian Lynskey and he was discussing how Orwell came under fire for what was seen as criticising his own side, but he was only saying what he saw as true. If a writer does not feel optimistic, should they strike an optimistic note to cheer people up or say what they believe at the potential expense of alienating their audience?

We are justified in being very pessimistic today. It isn’t to say we should not plan alternatives. It is possible to forestall these disasters. The question is: what are the odds of this happening?

In a paradoxical way, the pessimistic message may be the most optimistic, because the first stage of addressing an issue is to become aware of it. As J.G. Ballard said, if you see a road sign warning of dangerous bends ahead, you hit the brakes and avoid careering off the edge. I’m guessing that’s what animates the desire to write any dystopian literature.

We need the wake up call.

Prof. Greg Claeys. Thank you very much for your time.

If you enjoyed that interview and would like to find out more...

Greg Claey's book Dystopia: A Natural History is available via Amazon,

If you would like to hear more from Greg Claeys, please see the following links to YouTube for two of his talks:

Why are utopias important to mankind - Tedx Linz (28 June 2019)

From Utopia to Dystopia – St. Frances College (20 October 2017)

Leave a Reply